Know the basics of symptoms, diagnosis, and treatment to help you battle psoriatic arthritis.

Joint inflammation is all that is meant to be described by the general term arthritis. There are over a hundred different kinds of arthritis, and each one can have unique symptoms and triggers. As a result, arthritis is among the most prevalent chronic illnesses, impacting approximately a quarter of all adults in America, or 54 million people. However, not every type of arthritis is the same. Certain conditions, such as psoriatic arthritis, can be extremely painful and debilitating and are associated with immune disorders.

What is psoriatic arthritis?

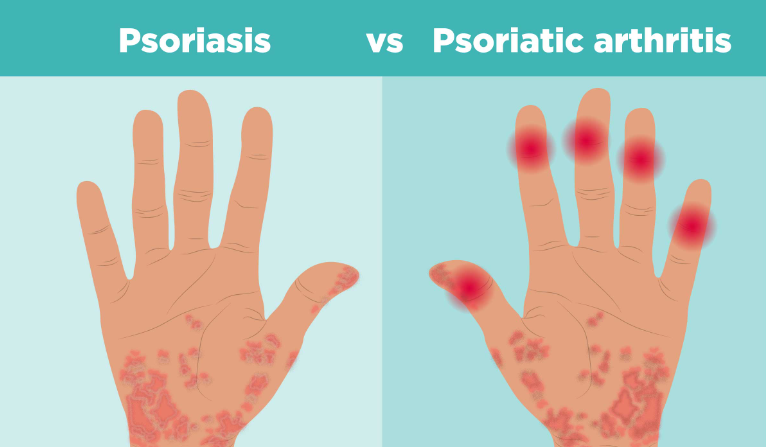

One of the many inflammatory types of arthritis, psoriatic arthritis, is linked to the common skin condition psoriasis. Psoriasis is a long-term skin condition that accelerates the skin cell life cycle. This results in a quick accumulation of cells on the skin’s surface, which gather into red, scaly patches. It can hurt a lot and be extremely itchy.

Of those with psoriasis, the Arthritis Foundation states that approximately 30% “also develop a form of inflammatory arthritis called psoriatic arthritis.” Similar to psoriasis, psoriatic arthritis is an autoimmune disease, which means that normal cells in the body are attacked by the immune system, resulting in pain, swelling, inflammation, and eventually joint damage.

Psoriatic arthritis is one of “a whole host of autoimmune conditions,” according to Dr. David Pugliese, a rheumatologist at Geisinger in Danville, Pennsylvania, that result in joint pain, swelling, and other complications. It’s critical to consult your doctor if you experience any joint pain or inflammation that seems similar to arthritis because “these conditions can give people arthritis and come with their own host of immune concerns that we need to monitor,” according to Pugliese.

Types

Within psoriatic arthritis, there are three main types. Symmetric psoriatic arthritis affects about 50 percent of patients, and it occurs in joints on both sides of the body. Asymmetric psoriatic arthritis affects about 35 percent of people with psoriatic arthritis. It’s generally considered the mildest form and tends to affect three or fewer joints. Three other types of psoriatic arthritis make up the rest of the cases. Arthritis mutilans occurs in the fingers and toes and is an advanced, deforming type of psoriatic arthritis. Spondylitis impacts the shoulders and neck. And distant interphalangeal predominant psoriatic arthritis impacts the joints at the ends of the fingers.

Symptoms

The Arthritis Foundation reports that “most people with psoriatic arthritis have skin symptoms before joint symptoms.” Skin symptoms of psoriasis include:

- Red patches of raised or inflamed skin.

- Whitish or silvery scales or plaques on those red patches

- Dry skin that cracks or bleeds.

- Tenderness, itching, or burning around the site of the patches.

- Thick, pitted, or ridged nails

- Swollen and stiff joints

But for some people, psoriatic arthritis can develop in the absence of any skin symptoms. “You don’t have to have psoriasis to have psoriatic arthritis,” says Dr. Esther Lipstein-Kresch, chief of rheumatology at ProHEALTH Care in New York. That can sometimes make diagnosis difficult, as the symptoms that accompany psoriatic arthritis may sometimes be similar to those of other forms of inflammatory arthritis.

Common symptoms of psoriatic arthritis include:

- Swollen, painful joints

- Joint stiffness, especially first thing in the morning.

- Sausage-like swelling along the length of the fingers or toes

- Tendon or ligament pain

- Reduced range of motion.

- Skin rashes and pitted nails

- Fatigue.

- Redness and irritation of the eyes and distorted vision.

Diagnosis

In order to determine whether you have psoriatic arthritis, your doctor will perform a comprehensive physical examination and obtain a long medical history. In order to determine the extent of inflammation in your body, your rheumatologist may also prescribe blood tests or X-rays of the ailing joints to examine the inside of them. To determine the degree of joint damage, you might also undergo CT, MRI, or ultrasound imaging.

Although there isn’t a specific blood test currently in use that can say definitively that you have psoriatic arthritis, your rheumatologist will likely order some blood tests to rule out other forms of inflammatory arthritis, such as rheumatoid arthritis. These tests look for an antibody in the blood called rheumatoid factor. Even if your RF test comes back negative, it doesn’t necessarily mean you don’t have rheumatoid arthritis. Lipstein-Kresch says that about 85 percent of people with rheumatoid arthritis will have a positive RF factor test but “the other 15 percent won’t. Those people have what’s called zero-negative RA.”

Even a positive RF test doesn’t completely rule out a diagnosis of psoriatic arthritis, as the two conditions can coexist, although the National Psoriasis Foundation reports that this coexistence of conditions is rare. Nevertheless, it’s important to work with a doctor who has experience treating arthritis conditions to be sure you’re arriving at the right diagnosis. “Even though we have some tools we use in terms of immunological testing that are helpful, ultimately (the correct diagnosis) still boils down to what the patient looks like on the exam and what kind of story they are telling,” Pugliese says.

Causes and risk factors

Psoriatic arthritis occurs when the body’s immune system misidentifies normal cells as foreign invaders and goes on the attack. The National Psoriasis Foundation reports that skin symptoms are present before the development of joint pain in about 85 percent of cases.

It’s not entirely clear why psoriatic arthritis develops in some people and not others, but genetics is likely part of the answer, as are environmental factors. People with a family history of either psoriasis or psoriatic arthritis are at higher risk of developing the disorder.

It’s believed that physical trauma or certain environmental factors, such as the introduction of a bacterial or viral infection, could sometimes trigger the immune response that develops into psoriatic arthritis in some people.

Age may also be a risk factor. Although anyone can develop psoriatic arthritis at any age, the Mayo Clinic reports that “it occurs most often in adults between the ages of 30 and 50.”

Treatment

Although there’s currently no cure for psoriatic arthritis, the condition can be managed. Patients may be offered a range of different medications, including:

- NSAIDs, or nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. NSAIDs lessen pain and inflammation. Some are available over-the-counter, such as naproxen sodium (Aleve) and ibuprofen (Advil, Motrin IB, etc.). For the purpose of easing psoriatic arthritis symptoms, your doctor might recommend stronger NSAIDs.

- Disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs) These drugs stall the progression of psoriatic arthritis and may be used to treat other forms of inflammatory arthritis. Methotrexate (Trexall), leflunomide (Arava), and sulfasalazine (Azulfidine) are three common DMARDs used to treat psoriatic arthritis.

- Steroids. Powerful anti-inflammatory steroids such as prednisone (Deltasone, Rayos, and Prednisone Intensol) can help bring down a flare-up of psoriatic arthritis or other inflammatory arthritis disorders quickly. Steroids have been around a long time and “are still excellent medications in terms of cooling things down,” Lipstein-Kresch says. “When you see somebody who is really inflamed and has a lot of pain, can’t sleep and can’t function, the steroids make a tremendous difference very rapidly.” But she says these are generally used sparingly as they can have some harsh side effects when used long-term. Steroids may also be used in combination with other medications to help prime the body’s response for the effects of biologics or other medications.

- Immunosuppressants. In immune disorders, the body’s natural defense mechanism, the immune system, works overtime and on the wrong targets. By tamping down some of this response, some patients may find some relief from autoimmune conditions such as psoriatic arthritis. Azathioprine (Imuran, Azasan) and cyclosporine (Gengraf, Neoral, Sandimmune) are two immunosuppressant drugs that may be used to treat the condition.

- Biologics. In the past decade, new medications have emerged to help patients deal with a number of inflammatory arthritis conditions. The NPF reports that these types of drugs are administered by injection or intravenous infusion and are derived from living cells cultured in a lab. Among these are:

- TNF-alpha inhibitors.These medications target tumor necrosis factor-alpha, an inflammatory substance produced by the body. By inhibiting the production of this substance, it may lead to reduced pain and stiffness and relief from joint swelling. Etanercept (Enbrel), infliximab (Remicade), and adalimumab (Humira) are three examples of this class of drug.

- Interleukin inhibitors.These drugs selectively target certain cytokines (a kind of protein) involved in inflammatory and immune responses. Examples include secukinumab (Cosentyx), ixekizumab (Taltz), brodalumab (Siliq), and ustekinumab (Stelara).

- T-Cell inhibitors.T-cells are a kind of white blood cell that creates inflammation in psoriatic disease. The drug abatacept (Orencia) may help tamp down some of this response.

- Few patients progress to the point of needing surgery, but it can be an option in some cases. In a procedure called synovectomy, your doctor might remove the damaged or diseased tissue from inside the joint. In other cases, a patient may undergo joint replacement surgery, joint resurfacing or realignment surgery or a bone fusion to relieve pain in a problematic joint.

Also read-Rheumatoid Arthritis : A Patient’s Guide To Rheumatoid Arthritis And Its Symptoms

images source: Google

Disclaimer: The opinions and suggestions expressed in this article are solely those of the individual analysts. These are not the opinions of HNN. For more, please consult with your doctor.