Amputees can regain a normal gait with the use of “smart” prosthetic legs; however, this is achieved via robotic sensors and algorithms that propel the limb forward at preset speeds.

Giving patients complete neurological system control over the limb would be a better approach, and an MIT research team claims to have achieved precisely that.

Researchers claim in the July 1 issue of the journal Nature Medicine that a fully normal walking gait, powered entirely by an individual’s own neurological system, can be restored using an experimental surgical method paired with a state-of-the-art robotic limb.

Also read-Where State-Level Abortion Laws Are Unaffected By Roe

prosthetic legs

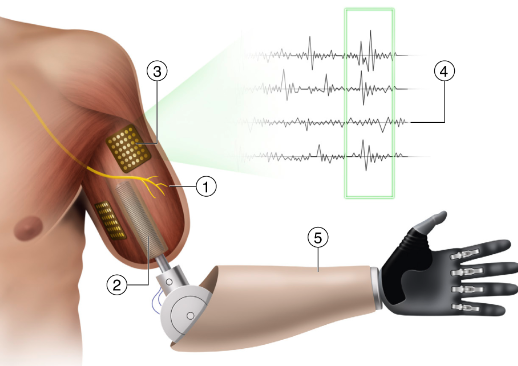

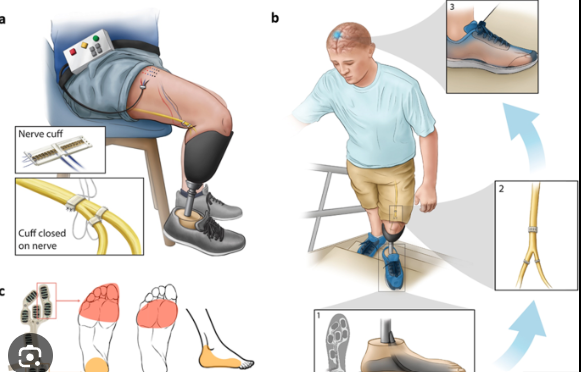

According to researchers, the process re-connects muscles in the residual limb, giving patients precise, instantaneous feedback on the posture of their prosthetic limb during gait.

Compared to those who had a standard amputation, seven patients who underwent this operation were able to walk more quickly, avoid obstacles, and climb stairs with considerably greater ease.

Hugh Herr, a senior researcher and co-director of MIT’s K. Lisa Yang Center for Bionics, stated, “No one has been able to show this level of brain control that produces a natural gait, where the human nervous system is controlling the movement, not a robotic control algorithm.”

According to background notes from researchers, pairs of muscles that alternately contract and extend control most arm and leg movement.

prosthetic legs

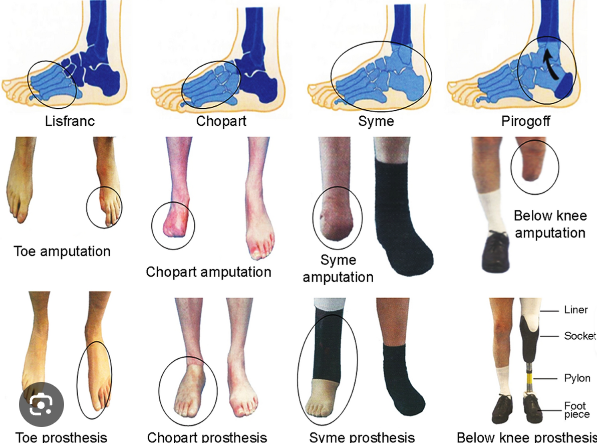

The interaction of these paired muscles is disrupted in a typical below-the-knee amputation, which makes it challenging for the nervous system to follow and govern movement.

Because they are unable to precisely detect the leg’s location in space, those who have that type of amputation have difficulty controlling a prosthetic limb. They can’t establish a walking gait or adapt to obstacles like slopes without the help of robotic controllers and sensors.

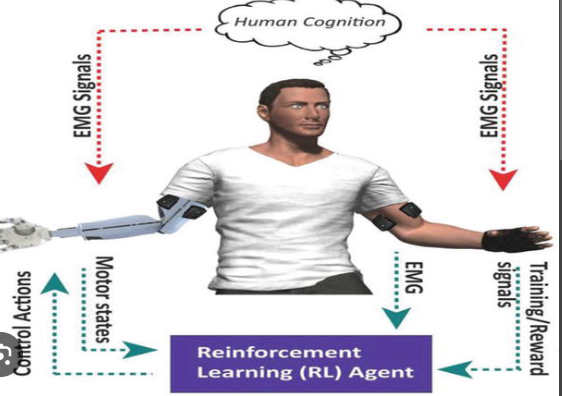

Herr and colleagues created what they refer to as agonist-antagonist myoneural interface (AMI) surgery, which enables people to achieve complete brain control over their prosthetic legs.

AMI surgery joins the two ends of the muscles rather than only severing muscle pairs. In the remaining portion of the leg, they are still able to interact with each other dynamically.

According to the experts, AMI surgery can be performed both during and after a first amputation.

A 2021 study by Herr’s lab found that the muscles of a limb treated with AMI surgery produced electrical signals similar to those emitted by their intact limb.

prosthetic legs

As a next step, the researchers started figuring out a way for those electrical signals to generate commands for a prosthetic limb and, at the same time, receive feedback from the limb about its position while walking.

That way, an AMI surgery amputee could both control a prosthetic leg and use the feedback to automatically adjust their gait as needed.

The new study shows that the sensory feedback does indeed translate into a smooth, near-natural ability to walk and navigate obstacles.

In the study, researchers compared seven AMI amputees with seven people who had traditional below-the-knee amputations.

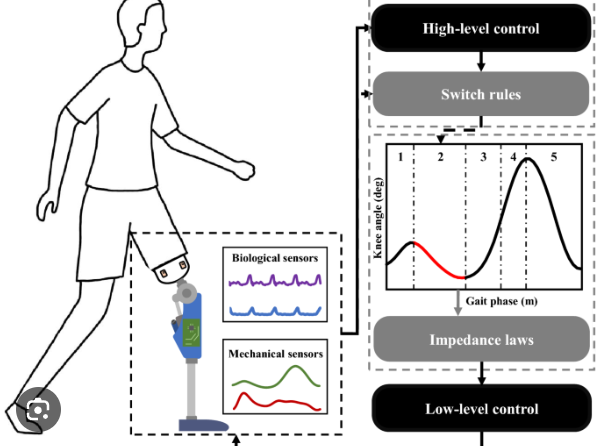

All participants used the same type of bionic leg: a prosthesis with a powered ankle, equipped with electrodes that can receive electrical signals from the major muscle groups of the leg.

These signals are fed into a robotic controller that helps the prosthesis calculate how much to bend the ankle, how much torque to apply and how much power to deliver.

prosthetic legs

Researchers tested all of the amputees with level-ground walking, walking up a slope, walking down a ramp, climbing up and down stairs and strolling on a level surface while avoiding obstacles.

Those who’d received the AMI amputation surgery were able to walk faster, at about the same rate as people without amputations.

They also navigated obstacles more easily and had more natural movement, as the results show. They were better able to coordinate the movement of their prosthetic limb with that of their natural limb, and they could push off the ground with about the same amount of force as someone without an amputation.

“The cohort that didn’t have the AMI was able to walk, but the prosthetic movements weren’t natural, and their movements were generally slower,” Herr said. in an MIT news release.

prosthetic legs

Interestingly, the improved movement occurred even though the amount of sensory feedback provided by AMI is less than 20% of that normally received by people who still have their full leg, researchers noted.

Lead researcher Hyungeun Song, a postdoctoral researcher in MIT’s Media Lab, stated, “One of the main findings here is that a small increase in neural feedback from your amputated limb can restore significant bionic neural controllability, to a point where you can allow people to directly neurally control the speed of walking, adapt to different terrain, and avoid obstacles.”

Herr hopes to “rebuild” human bodies in the end by creating a seamless and normal-feeling link between prosthetics and limbs.

The issue with the long-term strategy is that the wearer would never have a sense of embodiment from their prosthesis. According to Herr, they would never consider the prosthesis to be a part of their body or identity. “The strategy we’re using aims to fully integrate the human brain into electromechanics.”

prosthetic legs

Also read: July 4th: A Guide For People Taking Care Of Alzheimer’s Patients

images source: Google

Disclaimer: The opinions and suggestions expressed in this article are solely those of the individual analysts. These are not the opinions of HNN. For more, please consult with your doctor