Multifaceted treatment can restore healthy eating and reverse malnutrition of anorexia nervosa

An eating disorder called anorexia nervosa has the power to control and even endanger a person’s life. Parents of sons or daughters with anorexia feel powerless as they watch them lose weight at a time when their bodies should be growing and developing. People with anorexia are forced to avoid eating, skip meals with friends and family, and eventually suffer from the physical effects of malnourishment and starvation.

Anorexia may seem like a modern-day diagnosis, but it’s been around for a long time. “This is not a new condition that all of a sudden came about in the 20th century,” says Dr. Evelyn Attia, a professor of psychiatry and director of the Columbia Center for Eating Disorders at Columbia University Irving Medical Center in New York City. The term anorexia nervosa or similar names have been used to describe the problem since the mid-1800s. And the condition itself is much older.

Also read-GERD : A Patient’s Guide To GERD And Its Symptoms

Written case reports from as far back as the 1500s and 1600s appear to detail anorexia-like symptoms in individual patients, Attia notes. The book “Holy Anorexia” describes the case of St. Catherine of Siena, who had a condition strongly resembling anorexia in the late 1300s, including beginning to fast while still a teen in what’s been reported as an effort to change her appearance to avoid marriage and dedicate her life to religion. The author explores concepts such as the perceived moral superiority of eating as little as possible—or less—and extreme fasting as symbols of religious devotion.

Causes of anorexia nervosa

The understanding of anorexia’s causes is evolving. A change in its official definition seems to reflect awareness that untreated anorexia goes beyond an individual’s control rather than being a matter of willfulness or blame.

The previous version of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-4), an authoritative guide from the American Psychiatric Association, included this language in its anorexia nervosa criteria: “Refusal to maintain body weight at or above minimally normal weight for age or height (less than 85th percentile).”

However, the latest version, the DSM-5, removes blame from the individual to characterize anorexia: “Restriction of energy intake, relative to requirements, leading to a significantly low body weight in the context of age, sex, developmental trajectory, and physical health.”

Risk factors for anorexia nervosa

Anyone can develop anorexia and other eating disorders, regardless of their gender, age, or ethnicity. Nevertheless, some risk factors and life stages can increase a person’s susceptibility. These anorexia nervosa statistics are provided by the National Institute of Mental Health:

- The average age for anorexia to start is 18 years old.

- In adults, about 0.6% will develop anorexia in their lifetimes.

- Females have a threefold higher anorexia prevalence (0.9%) than males (0.3%).

- About 56% of people with anorexia have coexisting mental health disorders, such as anxiety, depression, and other mood disorders, impulse control disorders, or substance misuse.

- About one-third of people with anorexia seek treatment specifically for their eating disorder.

Symptoms of anorexia nervosa

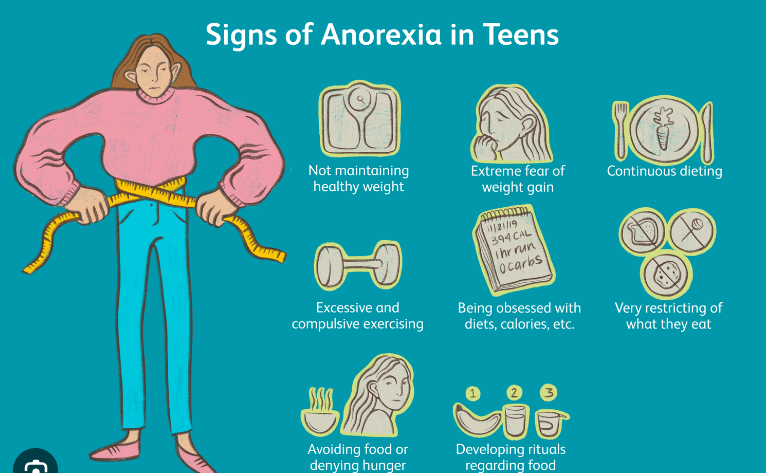

Although secretiveness is a common feature of eating disorders, family members and health care providers may pick up on red flags for anorexia nervosa like these:

- Drastic food restriction means consuming far fewer calories than needed.

- Changes in food choices, such as excessive avoidance of foods containing fat or carbs,

- Talking about weight continually.

- Preoccupation with weight, dieting, food, calories, and fat grams

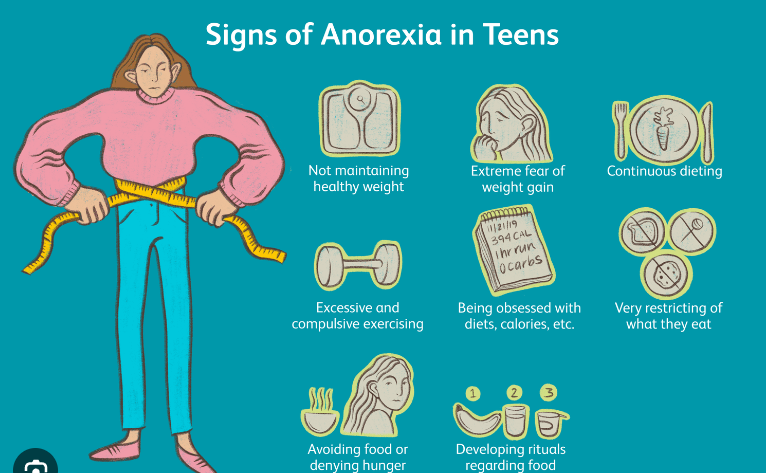

- Periodic comments about feeling overweight or fat, regardless of weight loss

- Dramatic weight loss.

- Weight loss or lack of weight gain in children or teens

- Wearing layers of clothing to conceal weight loss.

- Food rituals like separating foods on a plate.

- Emotional issues such as sadness and moodiness.

- Eating little or nothing.

- Avoid eating in front of others.

- Exercising to excess.

- Substance abuse.

Atypical anorexia, a subtype of anorexia, has similar symptoms except for one major difference: the person’s weight is within or above the normal range, even though he or she has lost a significant amount of weight.

Diagnosis of anorexia nervosa

When an eating disorder is possible, evidence-based screening tools can quickly reveal symptoms that should be followed up. One such tool is the brief SCOFF (Sick, Control, One, Fat, and Food) questionnaire. Patients respond to these items: whether you make yourself sick because you feel full, worry about losing control over what you eat, have recently lost more than 14 pounds (or one stone), think you’re too fat and believe that food dominates your life. Any health professional, such as a primary care provider or emergency room clinician, can ask these types of questions.

Treatments of anorexia nervosa

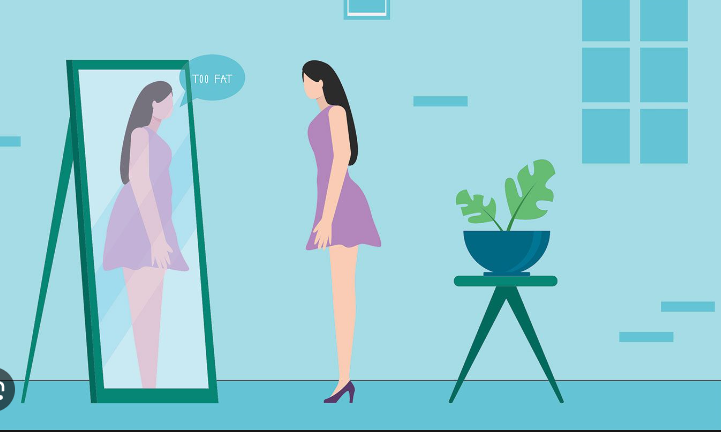

Because anorexia is a multifaceted condition with complex causes and a wide range of health effects, people may need multidisciplinary treatment from a variety of medical, psychological, and nutritional experts.

There are various levels of therapy for eating disorders and various settings where treatment can take place. These range from home-based and outpatient therapy to intensive outpatient therapy, residential therapy, partial hospitalization in which patients go home at night and in-hospital treatment.

Deciding which level of treatment is best for someone with anorexia is a process. For instance, if someone is interested in exploring the possibility of residential treatment, they should start by speaking with a member of the admissions team over the phone, says Stephanie Kern, clinical director of the Eating Disorder Solutions treatment center in Dallas.

Background questions Explore how long you’ve been struggling, whether you’re already working with an outpatient team, therapist, or dietitian, and a history of your eating behaviors, Kern says. That initial intake assessment usually reveals which level of care would best suit you. “You always want to treat somebody at the lowest (appropriate) level of care,” she adds. Someone who has been grappling with anorexia for more than 20 years is an example of a patient who might require care in a residential facility.

Also read-GERD : A Patient’s Guide To GERD And Its Symptoms

images source: Google

Disclaimer: The opinions and suggestions expressed in this article are solely those of the individual analysts. These are not the opinions of HNN. For more, please consult with your doctor.