Bulimia nervosa is an eating disorder that wreaks havoc on your body and mind.

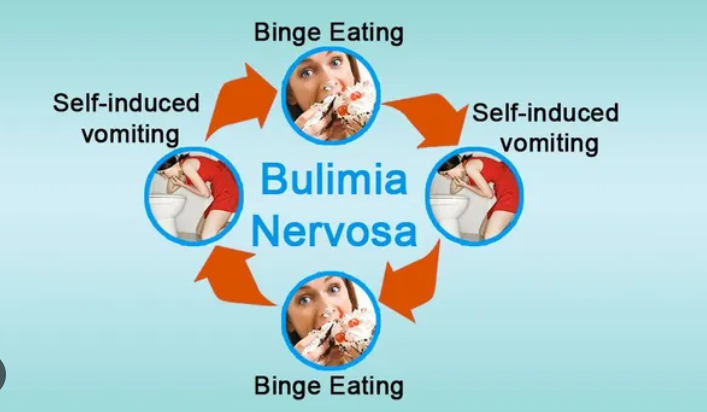

Bingeing and purging are two extremely unhealthy eating behaviors combined in bulimia nervosa. People who are experiencing a bingeing episode tend to overeat because they are unable to control their portion sizes. Purging is the process of eliminating the ensuing excess calories by using a range of techniques, including self-inflicted vomiting, laxative abuse, diuretics, or enemas.

Bulimia nervosa consumes a person not only in terms of their physical health but also in terms of their personality, behaviors, sense of self, capacity for function, and interactions with others.

Also read-Peptic Ulcers : A Patient’s Guide To Peptic Ulcers And Its Symptoms

Hiding all signs of your purging and stockpiling food for future binges can make you a habitually secretive person. Rather than sharing meals with others, you’re planning your early retreat into seclusion. You constantly worry that you’ll put on weight. It hurts to look in the mirror because you are critical of your appearance and accuse yourself of having defects. Because of this distorted perception of your body, you are unable to see yourself clearly.

The time you spend with bulimics interferes with your social life, career, and academic pursuits. You battle the underlying mental health conditions that underlie bulimic behaviors, such as stress, anxiety, and body-image issues, throughout all of this.

“Almost all patients attest to realizing that when they’re bingeing, purging, or restricting, it does give a sense of relief—temporarily,” says Dr. Terri Griffith, clinical coordinator of the intensive outpatient program at The Center for Eating Disorders at Sheppard Pratt in Baltimore. “But, unfortunately, it has a short shelf life, and afterward, all the emotions, problems, and difficulties are still there. So they are often like hamsters on wheels, having to continue those negative, maladaptive behaviors that don’t give them long-term relief.”

According to the National Eating Disorders Association, about 1.5% of women and 0.5% of men will develop bulimia nervosa over their lifetime. Fortunately, treatment is available to target these destructive behaviors and address related mental health challenges.

Causes of bulimia nervosa

Research on the origins of eating disorders such as bulimia is ongoing. The risk of bulimia nervosa has been linked to factors such as biology, genetics, social and cultural pressures, psychological problems, and emotional problems.

These elements raise the possibility of developing bulimia nervosa in particular, or eating disorders in general.

- Youth. Bulimia can happen at any age but tends to start in late adolescence or early adulthood. The average age for bulimia to begin is 18 years old, according to the National Institute of Mental Health.

- Sex. Teen girls and women are more likely to have bulimia than teen boys or men. However, bulimia is likely underdiagnosed in males. Men may be more reluctant to seek treatment because of guilt or shame and not wanting to open up about their problems, says Stephanie Kern, clinical director of the Eating Disorder Solutions treatment center in Dallas. Therefore, less evidence is available for researchers to analyze.

- Family history. If you have a close relative, such as a parent or sibling, with an eating disorder, that can increase your chances of having one, too.

- Biology. Having a high body mass index—a measurement that takes height and weight into account—is a risk factor for purging behaviors. Hormonal issues may contribute to bulimia development.

- Dieting. If you’re vulnerable, starting the cycle of dieting, losing weight, and then regaining it may get you into trouble with eating disorders.

- Emotional difficulties. Stress can trigger the urge to first binge, then purge. For example, being a member of a family experiencing financial strain may increase your risk of developing bulimia. Traumatic events can also act as triggers.

- Mental health conditions. Depression, anxiety, and substance use disorders have all been linked to eating disorders.

- Competitive sports. Activities that reward being thin, such as elite sports, dance, figure skating, horse jockeying, bodybuilding, gymnastics, wrestling, and modeling, are bulimia nervosa risk factors.

Symptoms of bulimia nervosa

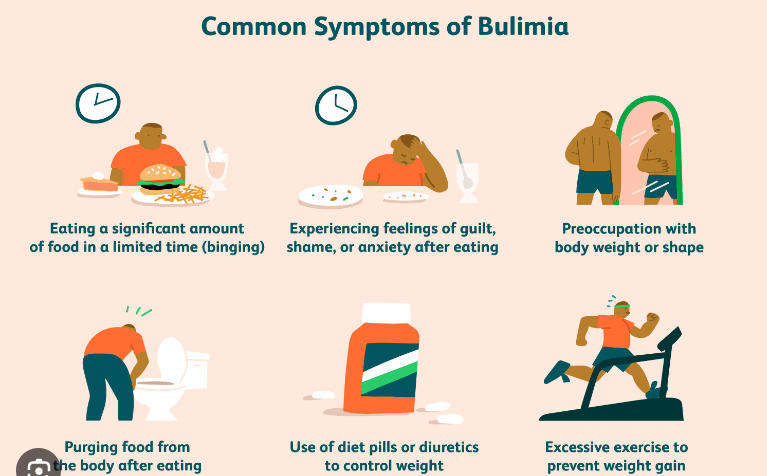

These are behavioral and emotional clues you may recognize in yourself or others with bulimia nervosa:

- Skipping meals or only eating small portions.

- Preoccupation with weight loss, dieting, and food control.

- Loss of control when eating.

- Eating even when feeling full.

- Immediately retreating to the bathroom after meals.

- Avoiding meals with others.

- Feelings of depression, anxiety, and shame after eating.

- Evidence of vomiting and frequent use of mouthwash or mints.

- Packages or empty wrappers of laxatives or diuretics.

- Excessive exercise.

- Difficulty concentrating.

Bingeing and purging can lead to a variety of physical problems, with symptoms like these:

- Significant weight fluctuations include both weight loss and weight gain.

- Sleep disruption.

- Stained, discolored, or shortened teeth.

- Raspy voice or cough caused by irritation from stomach acids with vomiting.

- Sores, pain, and swelling in the mouth or throat.

- Swollen salivary glands.

- Thinning, dry, or brittle hair.

- Fine, downy hair growth all over the body (lanugo).

- Hemorrhoids from blood vessel damage due to frequent purging.

- Stomach pain and acid reflux.

- Diarrhea or constipation.

- Bloating comes from fluid retention as your body tries to compensate for dehydration.

Diagnosis of bulimia nervosa

Your doctor will inquire about your medical history, eating habits, attitudes toward food, body weight and appearance, and any emotional problems you may be going through if they suspect you have an eating disorder such as bulimia nervosa.

You’ll also be assessed for mental health issues like substance abuse, obsessive-compulsive disorder, anxiety, depression, and self-harm like cutting that can occasionally coexist with eating disorders.

In addition, you may undergo a physical exam and have blood or urine tests, including the following:

- Blood chemistry is used to detect electrolyte imbalances like low potassium (hypokalemia) caused by repeated vomiting. In addition, low sodium (hyponatremia), low calcium (hypocalcemia), and low magnesium (hypomagnesemia) levels can be signs of laxative abuse. Blood tests can also indicate changes in liver or kidney function.

- A complete blood count will reveal signs of malnutrition, like anemia or low levels of healthy red blood cells.

- Urine tests are used to check for signs of dehydration or electrolyte imbalances.

- Additional heart tests or imaging tests of the bones, kidneys, or other organs are needed if related complications are suspected.

The latest version of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, an authoritative guide from the American Psychiatric Association, details the diagnostic criteria for bulimia nervosa. That includes detailing the frequency with which these related behaviors occur:

Recurrent episodes of binge-eating, which is defined as eating an amount of food during a discrete period of time—within two hours, for instance—that is definitely larger than what most people would eat during that period of time under similar circumstances,. Episodes include feeling unable to stop eating or to control how much you eat.

Treatments of bulimia nervosa

Bulimia nervosa treatment centers on psychotherapy. Evidence-based therapy options include the following:

- Cognitive-behavioral therapy. CBT is a form of counseling that helps people recognize unhealthy thought patterns that can lead to self-destructive behavior. It also guides people to more constructive and positive ways of thinking. Certain types of CBT have been adapted to treat eating disorders (CBT-E) and bulimia nervosa specifically (CBT-BN), which includes working with patients to reduce their negative or distorted self-image.

- Interpersonal psychotherapy. IPT is one-on-one therapy that centers on improving your relationships with other people. Therapy addresses current interpersonal issues (rather than past relationships), improving social functioning and support and reducing symptoms of distress. Studies suggest that IPT is as effective as CBT for treating eating disorders, although changes may be slower (but at least as long-lasting).

- Treatment is centered on the family. Adolescents with eating disorders, such as bulimia nervosa and anorexia, are the target audience for FBT. Parents are viewed as important resources in FBT because they can supervise meals, help kids revert to healthy eating habits, take charge of meal and snack options, and stop bingeing and purging. Children regain control over their eating habits gradually as they make progress.

- Intensive outpatient therapy. This can serve as a transitional form of treatment for patients who are medically and psychiatrically stable and can function at school, home, or work but still need to make progress toward recovery. For example, patients spend four hours a day, Monday through Thursday, at the intensive outpatient program that Griffith coordinates. They take part in group therapy, check in with their treatment team and have supervised dinner there.

- Partial hospitalization program. Although medically stable, patients with bulimia who are still engaging in daily bingeing or purging may need a PHP. At Sheppard Pratt, patients spend 12 hours per day in the partial hospitalization program, where they attend individual and group therapy sessions, have breakfast, lunch, and dinner, and then head home in the evening.

- Residential treatment facility. This live-in therapy takes place in a home-like environment intended to give residents a break from outside stress and focus on bulimia therapy. Residents are monitored during and after meals and snacks to observe eating behavior and prevent bingeing and purging. Individual and group therapy, ongoing mood assessment, and nutrition education are features of residential treatment. Residents’ progress determines their length of stay, which could last anywhere from a few weeks to several months. Insurance coverage may also be a factor in how long treatment lasts.

- Intensive inpatient treatment. This form of treatment, which takes place in hospitals or other medical facilities, is typically for people who are not medically or behaviorally stable. Many patients have complications from coexisting medical problems like diabetes. They may be suicidal or have rapidly worsening psychiatric symptoms. Some patients may require temporary tube-feeding or intravenous fluid to treat dehydration.

As patients make steady progress, they transition to less intensive models of care. Behavior change is the biggest sign of progress, Griffith says. Not letting emotions dictate how you eat, being receptive to therapy and adhering to medication regimens for psychiatric conditions are significant signs of improvement, she says. Maintaining your outside life and responsibilities, going to scheduled appointments and adapting what you’ve learned in treatment are all positive signs that you’re getting better at bulimia nervosa.

Also read: Peptic Ulcers : A Patient’s Guide To Peptic Ulcers And Its Symptoms

images source: Google

Disclaimer: The opinions and suggestions expressed in this article are solely those of the individual analysts. These are not the opinions of HNN. For more, please consult with your doctor.