Many patients can live seizure-free lives with the right diagnosis and treatment of epilepsy.

A brain disease called epilepsy is characterized by different kinds of seizures. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention estimate that approximately 3.5 million Americans—roughly 3 million adults and nearly 500,000 children—have active epilepsy.

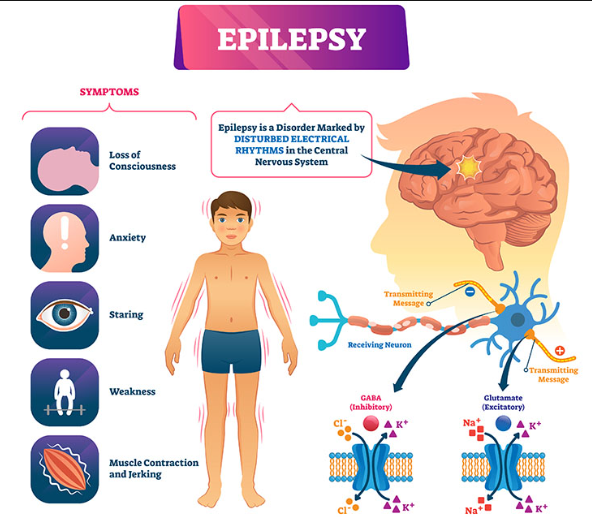

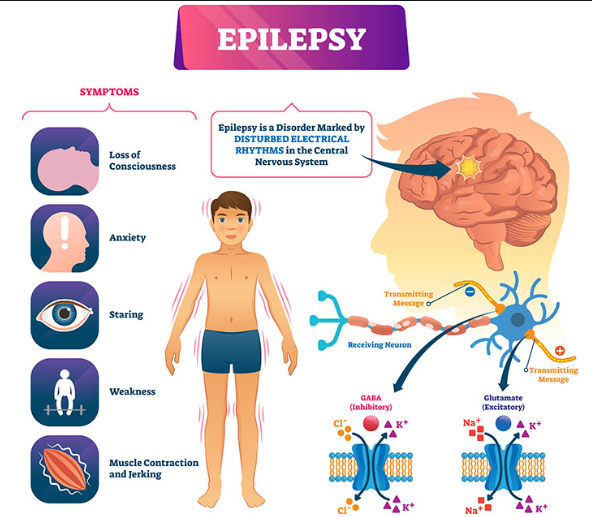

Different factors can cause seizures, but they always result from abnormal electrical activity in the brain. A seizure could be as mild as a brief period of time spent staring into space without making any sense. Or it might entail passing out, collapsing to the ground, and experiencing convulsions that cause your body to tremble. The precise definition of a seizure varies greatly.

Also read-Brain Tumors : A Patient’s Guide To Brain Tumors And Its Symptoms

Epilepsy is associated with a number of seizure types that vary in severity and symptomatology. However, epilepsy is not always diagnosed based on a single seizure. For example, a single febrile seizure (a seizure brought on by a high fever) does not satisfy the requirements.

Dr. Jerry Shih, the director of the Epilepsy Center at the UC San Diego Neurological Institute, states that seizures are discrete events, and a seizure is when a patient experiences an actual seizure attack. “Having seizures is, by definition, the condition known as epilepsy. Thus, to be diagnosed with epilepsy, you typically need to have two seizures.”

However, Shih adds, somebody who has had a seizure but clearly has several risk factors, such as a severe head injury, brain tumor, or stroke, and a high chance of having recurrent seizures, meets the epilepsy definition.

Unpredictability is among the most troubling aspects for people with epilepsy. They just don’t know when their next seizure will occur.

Some people with epilepsy have specific triggers that can bring on a seizure. Fatigue, stress, and alcohol are among the possible triggers.

Types of epilepsy

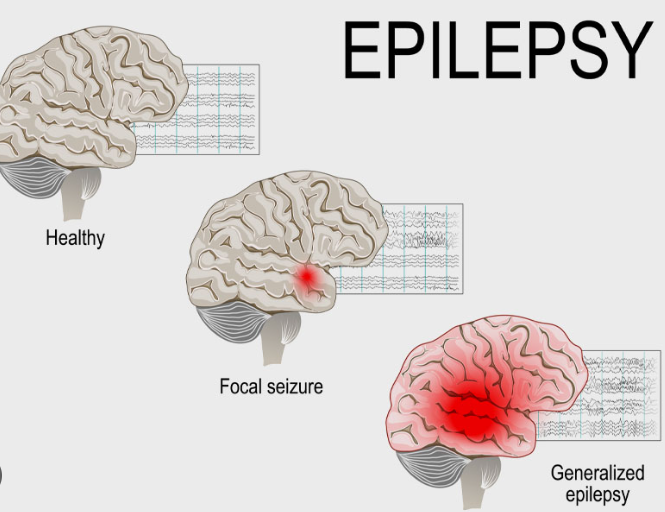

For practical purposes, conditions are divided into two major categories depending on the type of seizure involved: focal or generalized.

Focal Epilepsy

Focal or partial seizures involve seizure activity that’s limited to a part of either the left or right brain hemisphere. A specific site in the brain, or focus, can be identified as where the seizure begins. Types of focal seizures are:

- Simple focal seizures. Also called focal seizures with retained awareness, these involve twitching and sensory changes such as a strange smell or taste.

- Complex focal seizures. Also called focal seizures with loss of awareness, they leave a person feeling dazed or confused for several minutes or longer.

- Secondary generalized seizures These begin as focal seizures in one area of the brain but then spread to both brain hemispheres.

Generalized Epilepsy

Generalized epilepsy involves widespread seizure activity in both hemispheres of the brain. You may experience different types of generalized seizures, including:

- Absence seizures. Also called petit mal seizures, these lead to short periods of staring blankly or rapidly blinking.

- Convulsive or tonic-clonic seizures. Also called grand mal seizures, these lead to calling out, losing consciousness, falling to the ground, and muscle spasms or jerking.

- Clonic seizures. These involve shaking or jerking in parts of the body, lasting a few seconds to one or two minutes.

- Tonic seizures. Muscles suddenly become stiff in tonic seizures.

- Atonic seizures. Also called drop seizures or drop attacks, these involve muscles suddenly relaxing and losing strength, or tone. People go limp and may fall to the ground, but often stay conscious.

- Myoclonic seizures. These involve brief periods of jerking in parts of the body.

Other seizure types include:

- Seizures of unknown onset. These are unwitnessed seizures where it’s not clear when the seizure started.

- Psychogenic non-epileptic seizures. With PNES, attacks that appear similar to seizures are not caused by abnormal electrical activity in the brain, but are instead believed to have an underlying psychological basis.

Epilepsy affects children differently in terms of causes, effects and treatment. When it comes to a condition like epilepsy, Shih says, “Children are not little adults.” Childhood epilepsy also includes these conditions, among others:

- Benign partial epilepsy of childhood with centrotemporal spikes, or BECTS. This is also called “benign rolandic epilepsy” because it involves the rolandic area of the brain, which controls movement.

- Childhood absence epilepsy. This involves staring spells during which kids are unaware and unresponsive.

- Infantile spasm. Affecting infants starting at about 3 months to 12 months of age, it involves sudden stiffening throughout the body.

- Juvenile myoclonic epilepsy. Beginning in adolescences, it involves muscular jerking spells.

- Lennox-Gastaut syndrome. This describes multiple types of seizures. The child could experience both atonic and tonic seizures, for example.

- Landau Kleffner syndrome. Progressive loss of speech is a feature of this form of epilepsy.

According to various estimates, about 60% to 75% of children with benign epilepsy outgrow seizures after being gradually weaned off medication.

Causes

Brain injuries, including a stroke, trauma, a brain infection, or a brain tumor, can cause epileptic seizures. One example is a head injury that leads to scar tissue. “Those brain cells that survived the injury but are around the area of scarring are electrically unstable,” Shih says. “So they’re a little different than they were before the injury. When there’s a trigger, those cells become so unstable that they release this massive amount of electrical energy. That’s what a seizure is. It’s like a power surge going through your brain.”

By contrast, he says, people who have normal, electrically stable brain cells are unlikely to go into a seizure.

Some adults carry over epilepsy from childhood, often from a genetic or familial inheritance.

Symptoms

Focal

Symptoms of focal seizures can be subtle and may only be apparent to the person with epilepsy. Focal seizures include these symptoms:

- Staring. In focal-impaired awareness seizures, people stare blankly for a few seconds. In that moment, the person can’t speak, listen, or appear to comprehend before suddenly snapping out of it.

- Lip-smacking. Bystanders may also notice the person fluttering their eyelids.

- Stillness. Suddenly stopping activities or being very still could be an absence seizure sign.

- Unusual sensation. “Patients just have an unusual feeling, an unusual sensation, and then it passes,” Shih says. “And they recognize that, for whatever reason, they’ve lost a chunk of time.”

- Aura. Some people experience this rising feeling of an impending seizure.

Generalized

Generalized seizures put more stress on the body and are more obvious to bystanders. Tonic-clonic seizures, once known as grand mal seizures, have two phases that can include these symptoms:

Tonic Phase

- Muscle stiffening.

- Groan or cry.

- Loss of consciousness and falling.

- Tongue biting.

Clonic Phase

- Jerking of twitching of arms and legs, lasting several minutes.

- Blue or dusky face from breathing difficulty during seizure.

- Loss of bladder control.

- Slow return to consciousness.

- Tiredness, confusion or irritability afterward

Diagnosis

Determining whether you have epilepsy and the cause of your seizures is a multipart process.

History and Physical

Before any sophisticated testing, your diagnosis starts with a medical history. Your doctor will ask about every detail surrounding your seizure activity. Questions will include these areas:

- Before the seizure. You’ll be asked if you’ve experienced a recent illness, trouble sleeping or unusual stress. You’ll go over any medications you take: both prescription drugs and over-the-counter drugs. You’ll be asked about alcohol and substance use. You’ll describe what you were doing just before the seizure, such as whether you were sitting, standing or lying down or if you were doing strenuous physical activity.

- During the seizure. You’ll pinpoint when it happened and how it began. You’ll describe any warning signs, facial and body movements and your ability to speak and respond to others. You’ll talk about whether you lost consciousness. You’ll be asked about symptoms, such as losing bladder control or biting your tongue, and how long the seizure lasted.

- After the seizure. You’ll recall if you felt tired or confused. You’ll be asked if you could speak and respond normally, and how long it took to feel like you were back to yourself. You’ll describe any headache, muscle ache or other symptoms in the aftermath.

Because of the nature of generalized seizures, you may not know all of this firsthand. Eyewitnesses such as family members or friends can fill in the gaps. A written description, phone discussion or even a cellphone video could provide valuable information toward making the diagnosis.

Treatments

Medication is the first line of treatment for epilepsy. Some drugs only treat focal seizures, others only treat generalized seizures and some work for both types. This is partial list of anti-epilepsy drugs:

- Depakene and Depakote (valproic acid).

- Dilantin (phenytoin).

- Epidiolex (cannabidiol or CBD).

- Klonopin (clonazepam).

- Lamictal (lamotrigine).

- Neurontin (gabapentin).

- Phenobarbital (generic).

- Tegretol (carbamazepine).

- Topamax (topiramate).

- Zonegran (zonisamide).

Effectiveness for specific seizure types, short- and long-term side effects, drug interactions, and safe use in pregnant women vary widely among anti-epilepsy drugs. Effectiveness and tolerability also vary from patient to patient. Your doctor should talk with you about the risks and benefits of any epilepsy drug before prescribing it.

Also read-Alzheimer’s Disease: A Patient’s Guide To Alzheimer’s Disease And Its Symptoms

images source: Google

Disclaimer: The opinions and suggestions expressed in this article are solely those of the individual analysts. These are not the opinions of HNN. For more, please consult with your doctor.