ICC World Cup 2023: Sporting events may bring the world together and deliver economic benefits to host countries, but they also raise carbon emissions. The ongoing ICC Men’s Cricket World Cup 2023, which India is hosting, could follow suit.

With the ICC Men’s Cricket World Cup started, the tension and expectation are obvious, and with good reason. India won the Cup the previous time it hosted it in 2011. Indeed, the two succeeding hosts, Australia in 2015 and England in 2019, both won the Cup, bolstering the host’s expectations. The Indian team’s powerful lineup, which includes Rohit Sharma, Virat Kohli, Hardik Pandya, Ravindra Jadeja, Mohammed Shami, and Jasprit Bumrah, has also contributed to their excitement.

And over 2.48 million spectators are scheduled to visit India to see the 48 matches between 10 countries, which will be played in stadiums across 10 cities over 46 days between October 5 and November 19. With such attendance, the competition is expected to benefit both the Indian economy and the Board of Control for Cricket in India (BCCI).

There are no regulations in India requiring…reporting, or control measures with respect to GHG emissions for sporting events, except when [it] may be covered under another

regulation

BOSE VARGHESE

SR. DIRECTOR–ESG,

CYRIL AMARCHAND MANGALDAS

But, despite all of the enthusiasm, one factor must be considered: the Cup’s carbon imprint. Although the event’s projected carbon emissions have not been officially calculated, industry experts estimate that it could rival the emissions seen at the FIFA World Cup Qatar 2022, which were estimated to be around 3.6 million tonnes of carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions, or the equivalent of 1.34 billion litres of diesel, according to the US Environmental Protection Agency’s calculator. However, no plans to offset such emissions have been announced.

“The Cricket World Cup will not be anything less unless sustainable measures are taken,” says Ajay Pillai, Partner for Risk Advisory at Deloitte India. He emphasizes that, while there are fewer matches in this competition than in football, a 50-over cricket match lasts longer. Most are day-night matchups that necessitate floodlights, substantial travel for the teams, and a large crowd.

Tricky Calculations

The first major obstacle in tackling this issue is calculating the carbon footprint. The complexities of carbon emissions are exacerbated by their multifarious nature—from varied sources to data availability, time considerations, indirect emissions, and behavioral implications, to mention a few.

Every event has a distinct carbon footprint that is determined by a variety of elements, including the materials used in building or restoration, the energy needed for lighting and air conditioning, transportation, and so on. “It’s important to note that the precise carbon footprint estimates for a specific event can vary greatly depending on the host country’s infrastructure, transportation systems, and energy sources,” says Jagjeet Sareen, a climate expert with management consulting firm Dalberg Advisors.

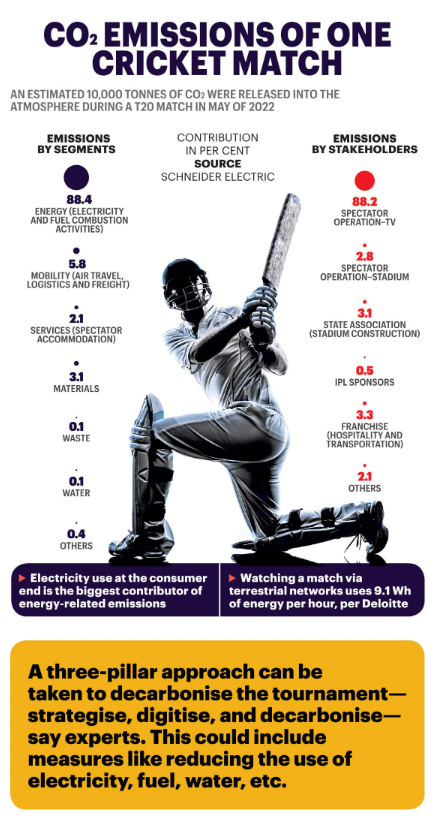

In India, such an analysis was conducted. Last year, Schneider Electric and the Rajasthan Royals of the Indian Premier League (IPL) calculated the carbon footprint of one T20 match at around 10,000 tonnes of CO2 equivalent—or about 3.72 million litres of diesel—and this was when the tournament was played in only two cities due to Covid-19 and had a low carbon footprint.

This enabled the Rajasthan Royals and Schneider Electric to organize a carbon-neutral match using an emission offset approach. Schneider Electric agreed to partner with other authorities to plant 17,000 trees over six months to trap CO2 emissions over a 30-year period, making that specific match carbon neutral by 2052.

Consider the magnitude of the Cricket World Cup. It necessitates substantial travel for teams, support workers, and supporters from both abroad and within India. Furthermore, most matches necessitate the use of floodlights. Furthermore, the event will generate significant waste in the form of water, food, and plastics due to complex logistics. Furthermore, millions of fans will tune in to watch and stream these matches on devices such as televisions, mobile phones, and laptop computers. When all of these factors are combined, the resulting footprint is enormous.

The International Cricket Council (ICC), cricket’s global governing body, is well aware of this. According to a spokesperson, “The ICC is still developing a global sustainability strategy for the sport, and as a part of that, it undertook a carbon footprint audit of the ICC Men’s T20 World Cup 2022 and will do the same for the ICC Men’s Cricket World Cup 2023 so we can understand the environmental impact of our events and have a baseline from which to work in reducing our footprint.”

A number of sustainability efforts are said to be ongoing. “This includes installing plastic recycling machines at each venue, with the waste being turned into ICC staff clothing for future events.” “There is a waste management project in collaboration with Coca-Cola and United Way Mumbai that includes waste segregation and landfill reduction,” an ICC representative adds.

Some of the ICC’s official partners have also announced sustainability initiatives. Booking.com, the tournament’s official accommodation partner, is ensuring that visitors looking to watch a game can book sustainable accommodations. “Our travel sustainable badge will help provide the necessary information to travellers who wish to make sustainable travel choices for the ICC Men’s Cricket World Cup,” says Santosh Kumar, Country Manager for India, Sri Lanka, the Maldives, and Indonesia at Booking.com. In India, we currently have over 20,000 establishments that have been recognized for their sustainability efforts.” Other partners such as BIRA 91, MRF, Byju’s, BharatPe, Nissan, Oppo, and Aramco did not respond to inquiries.

However, it introduced a “Go Green” initiative during this year’s IPL, promising to plant 500 trees for every dot ball bowled in the playoff round. Separately, BCCI Secretary Jay Shah tweeted on X on September 29: “We’ve partnered with @TataCompanies in an eco-friendly endeavor to plant 147,000 saplings.” The historic 100,000th seedling was planted at the landmark Narendra Modi Stadium, exemplifying our dedication to Mother Earth.”

Catch 22

For India, the Cup comes at an interesting time. In recent years, India has taken the lead in terms of sustainability. In 2014, it became the first country to require firms to practice corporate social responsibility (CSR), which requires enterprises to devote at least 2% of their net income to societal causes such as poverty reduction, gender equality, and environmental protection.

Following that, the Securities and Exchange Board of India (Sebi) introduced the Business Responsibility and Sustainability Reporting framework in May 2021, requiring the top 1,000 listed entities by market capitalisation to report on sustainability-related aspects in their annual financial report submitted to Sebi beginning with fiscal year 2022-23 (FY23). Later that year, during the COP26 summit in Glasgow, Prime Minister Narendra Modi committed to achieving net-zero emissions by 2070.

However, one gap is the lack of precise rules governing greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions from athletic activities.

“There are no regulations in India requiring monitoring, reporting, or control measures with respect to GHG emissions for sporting events, except when a particular GHG may be covered under another regulation due to its toxicity, health hazard, or other impacts,” says Bose Varghese, Senior Director-ESG at Cyril Amarchand Mangaldas. Furthermore, he argues, CSR regulations only apply to businesses. Federations are not included.

Of course, the event organizer can make proactive announcements about activities. According to Sareen of Dalberg Advisors, there are various international approaches that Indian organizers might emulate. “These include ISO 20121: Event Sustainability Management System, an international standard that provides a framework for managing the social, economic, and environmental impacts of an event, including measures to address climate change,” he said.

The UNFCCC Sports for Climate Action Framework also encourages organizations to develop a strategy to attain climate neutrality for their events. The Green Sports Alliance provides resources and guidance on sports sustainability; the Carbon Trust Standard for Sport certification program assists sports organizations and venues worldwide in measuring, managing, and reducing carbon emissions; and the Global Reporting Initiative provides sustainability reporting standards.

Loads to do

While the ICC’s and its official partners’ initiatives, including as Booking.com and stadiums, are a solid start, they may not be enough. To decarbonize the tournament, Deepak Sharma, Zone President, Greater India, and MD & CEO Schneider Electric India, suggests a three-pillar approach: strategize, digitize, and decarbonize. It should begin by devising a strategy for measuring the carbon footprint and creating a road map for decarbonization. The next phase is to digitize resource consumption and monitor pollution. Schneider Electric’s digital solutions, for example, have been utilized in many stadiums across the world, including the Melbourne Cricket Ground (MCG) in Australia, to help reduce emissions.

“In the MCG, with our complete range of solutions, we have helped [it] discover up to 50 per cent energy-saving opportunities along with safer and improved asset management,” says Sharma.

Finally, a decarbonization action plan that includes lowering the usage of resources such as energy, fuel, water, and so on must be implemented. It should be considered to avoid on-site diesel generators. While little can be done to reduce the emissions caused by air travel during the tournament, locals should be provided with free access to public transportation (including metro) for all ticketholders and accredited workers. This might be combined with e-vehicles for the movement of officials and players, as was done at the maiden MotoGP Bharat event in Uttar Pradesh in September. Bottles manufactured from recycled plastic could also be considered for drinks served at stadiums or elsewhere.

Also Read: Vedanta Q2 Results: Net Loss Of Rs 1,783 Crore Compared To Profit Of Rs 1,808 Crore In Q2 FY23

image source: google