Early intervention and warding off urinary tract infections are key to preventing complications of Kidney Reflux

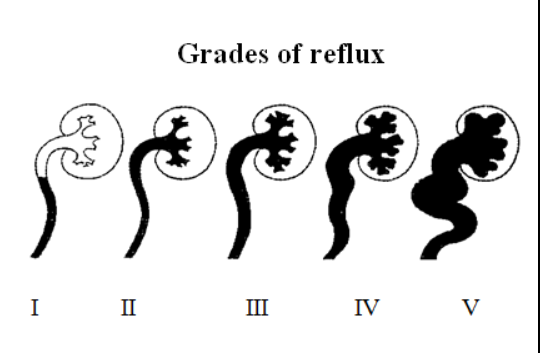

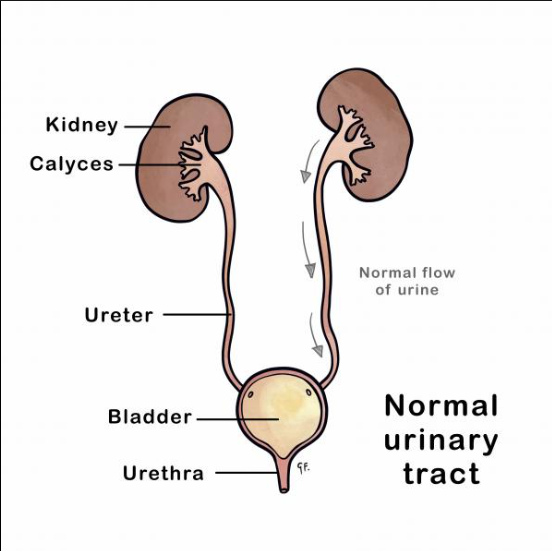

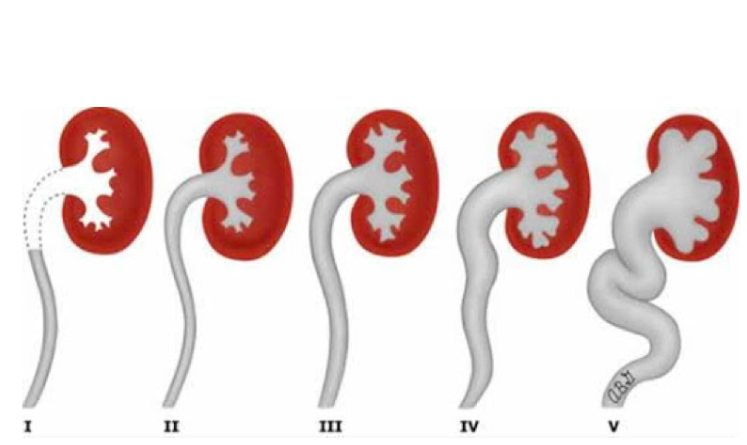

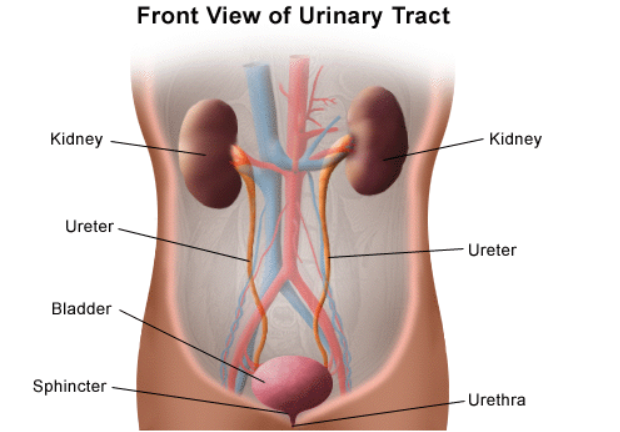

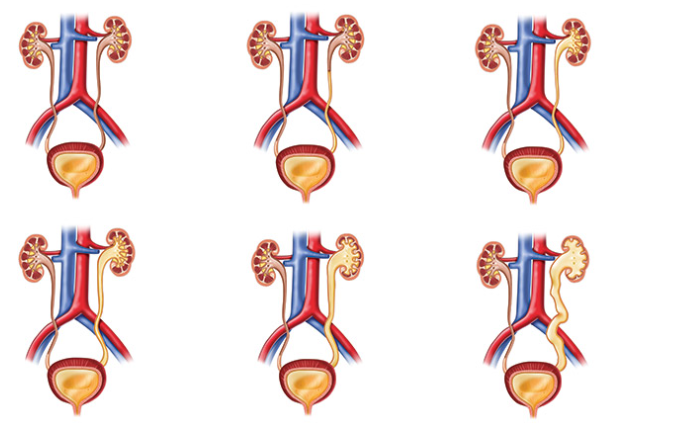

Urine should only flow in one direction through the body; it should start at the kidneys and continue southward through the urinary tract. Urine flow, however, can occasionally reverse and return to the kidneys. Although it can be detected at any age, this kidney reflux into the kidneys, also known medically as vesicoureteral reflux, or VUR, is usually discovered in our early years. Based on available data, kidney reflux affects approximately 2% of girls and 0.6% of boys. Because the symptoms appear early, it primarily affects infants and young children. Additionally, it is occasionally detected through prenatal imaging, according to Dr. Audrey Rhee, the Cleveland Clinic’s director of pediatric urology.

Also read-Heart Arrhythmias : A Patient’s Guide To Heart Arrhythmias And Its Symptoms

Complications of kidney reflux

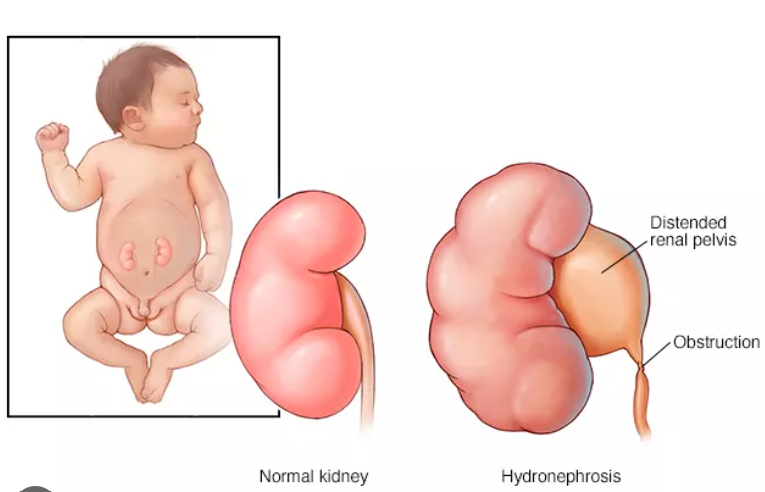

Urine yo-yoing between the kidneys and the bladder is not the problem with kidney reflux; most people are unaware that reflux is happening, and it is painless. The issue is that kidney reflux increases the growth of bacteria in the urinary tract, which raises the risk of recurrent UTIs significantly. An infection of the lower urinary tract may affect the bladder and urethra, while an infection of the upper urinary tract may affect the kidneys and ureters.

A urinary tract infection (UTI) in a healthy adult or child is generally considered benign. However, kidney infections are far more dangerous and can occur if the contaminated urine refluxes up into the kidney, according to pediatrician Dr. Nathan Beins.

Symptoms

Kidney reflux doesn’t have symptoms, but urinary tract infections do. And that’s what typically lands people with kidney reflux in a doctor’s office.

Symptoms of lower urinary tract infections include:

- Pelvic pain.

- Increased frequency or urgency to urinate.

- Burning during urination.

- Cloudy or dark urine.

- Foul-smelling urine.

Diagnosis

To check for a urinary tract infection, doctors first need a sample of urine for a urinalysis. Because infants aren’t yet able to void on command, a urine sample is collected with a catheter, a long tube inserted into the bladder. Young children with the same inability to void on command can wear a special bag that catches urine as it’s released.

Once a urine sample is collected, it’s tested (with a dipstick) for white blood cells and other signs that might indicate infection. If the test suggests bacteria are present, the urine sample is sent to a lab where the bacteria are grown (a test called a urine culture) to determine the kind of bacteria causing the infection. That helps doctors tailor treatment for the infection, which typically involves a 7- to 14-day course of antibiotics.

Treatment

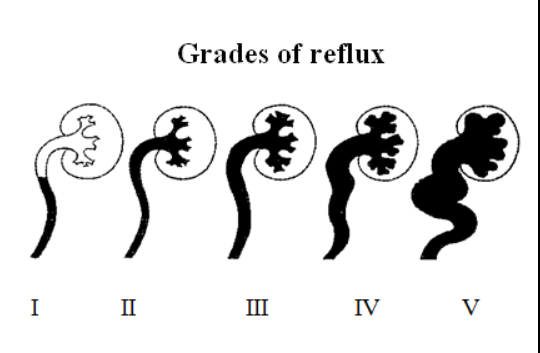

- A wait-and-watch strategy. Apart from taking lifestyle management measures to prevent further UTIs, treating the initial UTI in children with low-grade kidney reflux with a brief course of antibiotics may be all that is required. According to Rhee, “there isn’t much more to do because kids will outgrow it.” “Over time, the ureter’s tunnel in the bladder will grow longer.”

- Control of one’s lifestyle. All children with kidney reflux, especially those with bladder-bowel dysfunction, can benefit from lifestyle management. Austin explains, “It entails counseling, journaling, relaxation techniques, scheduled voiding, and a diet high in fiber and fluids.” “You want to make sure they don’t put off voiding or become constipated.”

- Long-term antibiotics use. For kids with high-grade kidney reflux, the condition is trickier to treat. Management can involve long-term, low-dose antibiotics as a preventive tool to ward off repeat urinary tract infections. This is called antibiotic prophylaxis. But it comes with the risk of antibiotics resistance in the future. Is it worth it? Research suggests that antibiotic prophylaxis does help prevent recurrent urinary tract infections, but does not necessarily prevent scarring in the kidneys. “You’d have to treat eight kids for two years to prevent one infection. That’s a lot of antibiotics for what might be potentially small benefits. But if we restrict antibiotic prophylaxis, then some kids who aren’t on it may develop lots of UTIs and develop scarring,” Beins points out. Rhee agrees it’s a delicate balance. “There isn’t an easy answer,” she says. “If I were to give someone an antibiotic, I wouldn’t give them the ‘big gun’ antibiotic. And you don’t have to be on prophylaxis indefinitely. You can stop after a year or six months to see how the child does.”

Also read-Enlarged Heart : A Patient’s Guide To An Enlarged Heart And Its Symptoms

images source: Google

Disclaimer: The opinions and suggestions expressed in this article are solely those of the individual analysts. These are not the opinions of HNN. For more, please consult with your doctor.