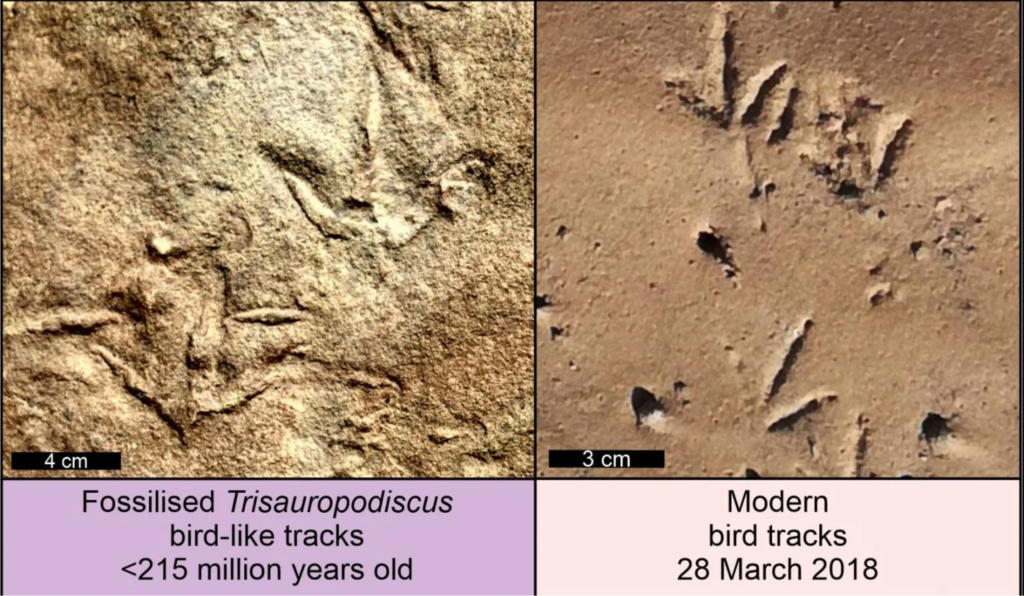

The discovery of ancient three-toed footprints in southern Africa has sparked a scientific debate about the identity and evolution of the animals that left them. The footprints, known as Trisauropodiscus, date back to over 210 million years ago, during the Late Triassic Period, and are similar to those of modern and fossil birds. However, they are 60 million years older than the oldest known bird fossils, raising the question of whether they belong to early dinosaurs, near-bird ancestors, or other reptiles that independently evolved bird-like feet.

The Enigmatic Footprints

A team of researchers from the University of Cape Town in South Africa has conducted a comprehensive study of the Trisauropodiscus footprints, which are found in numerous fossil sites in Lesotho and South Africa. The researchers examined the physical characteristics and variations of the footprints, as well as the geological and paleontological context of the sites. They also compared the footprints with those of other known animals from the same region and time period, as well as with those of modern and fossil birds.

The researchers identified two distinct types of Trisauropodiscus footprints, which they named Trisauropodiscus gracilis and Trisauropodiscus robustus. The former is smaller and more slender, and resembles the footprints of certain non-bird dinosaurs, such as theropods and ornithischians. The latter is larger and more robust, and resembles the footprints of birds, such as ostriches and emus. Both types have three forward-pointing toes, with a long middle toe and a short inner and outer toe. They also have a small backward-pointing toe, or hallux, which is characteristic of birds and some near-bird dinosaurs, such as Archaeopteryx.

Also read : 860 Volts Of Surprise: Unraveling The Peculiar Genetic Impact Of Electric Eels

The researchers concluded that the Trisauropodiscus footprints do not match any of the known fossil animals from the Late Triassic of southern Africa, such as the early dinosaurs Massospondylus and Euskelosaurus, or the crocodile-like reptiles Erythrosuchus and Euparkeria. They also ruled out the possibility that the footprints belong to true birds, as they are too old and too different from the earliest bird fossils, such as Archaeopteryx and Confuciusornis, which date back to the Late Jurassic and Early Cretaceous Periods, respectively.

The researchers proposed that the Trisauropodiscus footprints could have been produced by early dinosaurs, possibly even members of a near-bird lineage, that had convergently evolved bird-like feet. They suggested that these animals may have been adapted to living in forested environments, where they used their feet for grasping branches and perching on trees. They also speculated that these animals may have been related to the coelophysoids, a group of small and agile theropod dinosaurs that lived in the Late Triassic and Early Jurassic Periods, and that some of them may have given rise to the avian lineage.

However, the researchers also acknowledged that there could have been other reptiles, cousins of dinosaurs, that had independently evolved bird-like feet, and that they could not rule out this possibility without finding the body fossils of the Trisauropodiscus trackmakers. They also noted that the Trisauropodiscus footprints are not the only evidence of bird-like features in the Late Triassic of southern Africa, as there are also fossil bones of Scleromochlus, a small reptile that had long legs and a long tail, and that may have been capable of gliding or even flying.

The study, published in the journal PLOS ONE, is the first to provide a detailed and comprehensive analysis of the Trisauropodiscus footprints, and to reveal their similarity to bird footprints. The study also adds to the growing knowledge and appreciation of the diversity and complexity of the Late Triassic fauna of southern Africa, which is one of the richest and most important sources of information on the origin and evolution of dinosaurs and other reptiles. The study also challenges and enriches the understanding of the origin and evolution of birds and their ancestors, and shows that the history of bird-like features is more ancient and more complicated than previously thought