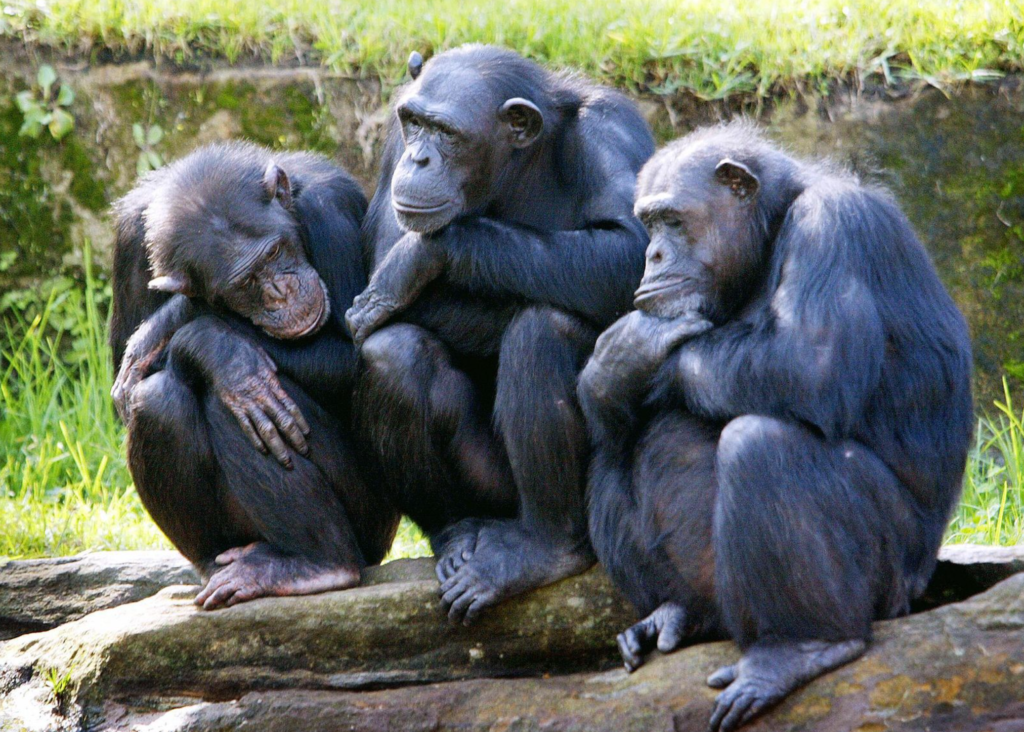

Menopause, the cessation of reproductive function in females, is a rare and puzzling phenomenon in the animal kingdom. Among mammals, only a few species of toothed whales and humans are known to have substantial post-reproductive lifespans, in which females live for decades after they stop reproducing. The evolutionary reasons for this trait are still debated, but some hypotheses suggest that it is related to the social and ecological benefits of having older females who can help their offspring and kin survive and reproduce. However, a new study published in the journal Science has challenged this view, by showing that menopause and post-reproductive survival are not unique to humans and whales, but also occur in a population of wild chimpanzees in Uganda.

Menopause in Wild Chimpanzees

The study, led by Brian Wood from the University of California, Los Angeles, is based on two decades of research on the Ngogo community of wild chimpanzees in Kibale National Park, western Uganda. The Ngogo community is one of the largest and best-studied groups of chimpanzees in the world, with more than 200 individuals and a long-term database of demographic and physiological data. The researchers analyzed the reproductive histories and hormone levels of 100 female chimpanzees, and found that 34 of them experienced menopause, defined as the permanent cessation of ovarian cycling, at an average age of 43 years. Moreover, 18 of these females survived for more than 10 years after menopause, reaching an average age of 55 years.

Also read : Why Don’t Metals Burn? Unveiling The Fire-Resistant Nature Of Metallic Elements

The discovery of menopause and post-reproductive survival in wild chimpanzees is surprising and unprecedented, as it contradicts the previous observations and assumptions about the reproductive patterns and lifespans of chimpanzees and other primates. Previous studies of wild chimpanzees in other sites, such as Gombe and Mahale in Tanzania, have shown that female chimpanzees usually die shortly after they stop reproducing, and that they rarely live beyond 50 years. Similarly, studies of captive chimpanzees and other primates have shown that they have a short or negligible post-reproductive lifespan, and that they do not exhibit the hormonal changes associated with menopause in humans.

The researchers suggest that the occurrence of menopause and post-reproductive survival in the Ngogo chimpanzees may be explained by a combination of ecological and social factors that are unique to this population. First, the Ngogo chimpanzees live in a rich and stable environment, where they have abundant and diverse food resources, and where they face low predation and disease risks. This may allow them to have higher survival and fertility rates, and to live longer than other chimpanzee populations. Second, the Ngogo chimpanzees live in a large and cohesive social group, where they have strong bonds and alliances with their relatives and friends, and where they have low levels of aggression and stress. This may provide them with social support and protection, and may also reduce the costs and increase the benefits of having older females in the group.

The researchers also suggest that the discovery of menopause and post-reproductive survival in wild chimpanzees may have important implications for understanding the evolution of this trait in humans and other mammals. The finding challenges the idea that menopause and post-reproductive survival are exclusive to humans and whales, and that they are linked to specific social and ecological features, such as grandmothering, culture, and language. The finding also supports the idea that menopause and post-reproductive survival are more widespread and variable than previously thought, and that they may have evolved independently and convergently in different lineages, under different selective pressures and constraints.

The study, published in the journal Science, is the first to document menopause and post-reproductive survival in wild chimpanzees, and to reveal the hormonal and demographic mechanisms of this phenomenon. The study also adds to the growing knowledge and appreciation of the diversity and complexity of the reproductive patterns and lifespans of chimpanzees and other primates, and of the factors that influence them. The study also challenges and enriches the understanding of the origin and evolution of menopause and post-reproductive survival in humans and other mammals, and shows that this trait is more ancient and more complicated than previously assumed.

Also read : Researchers Find That Bees Are Faster And Better Decision-Making Than Humans